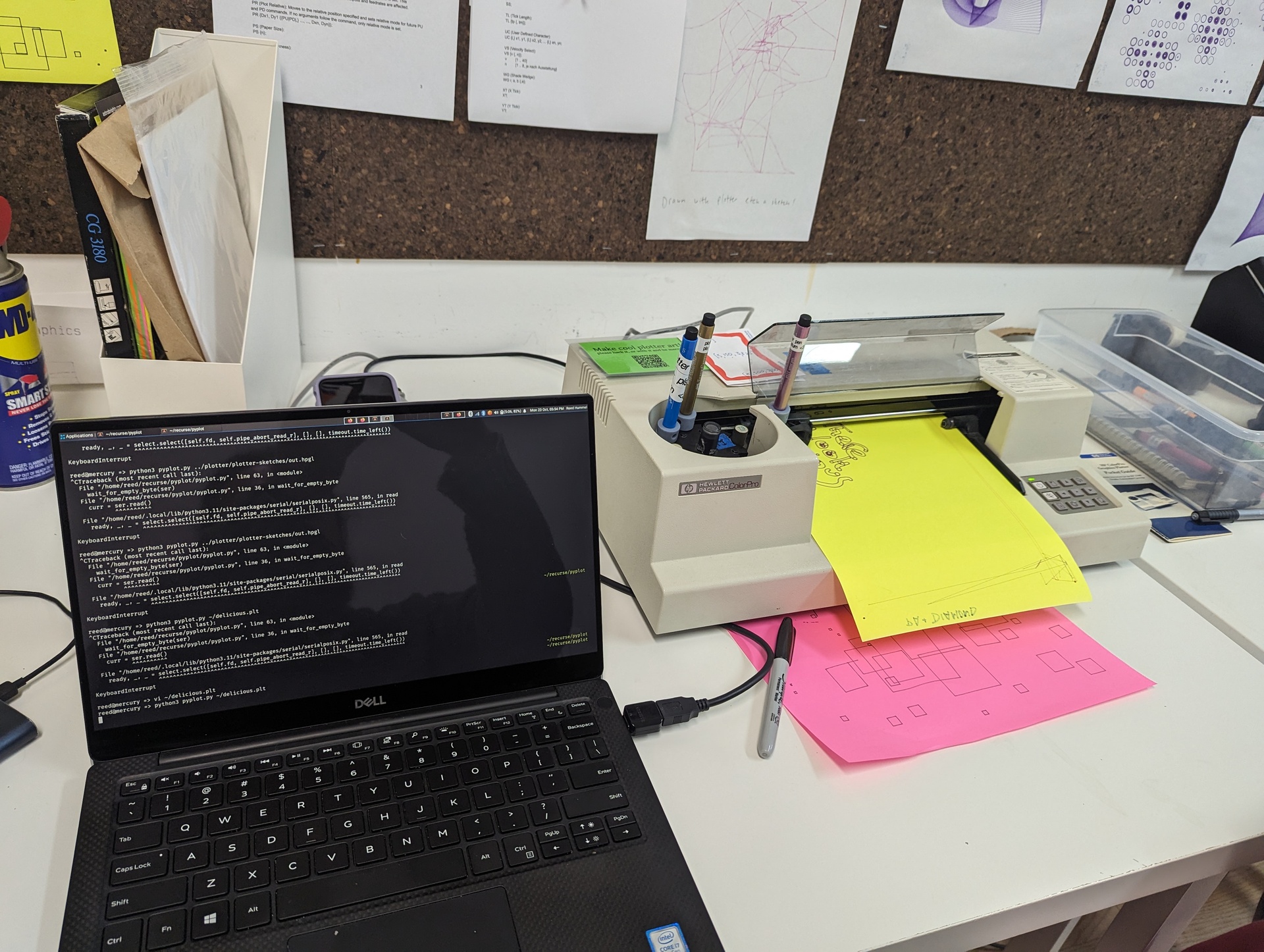

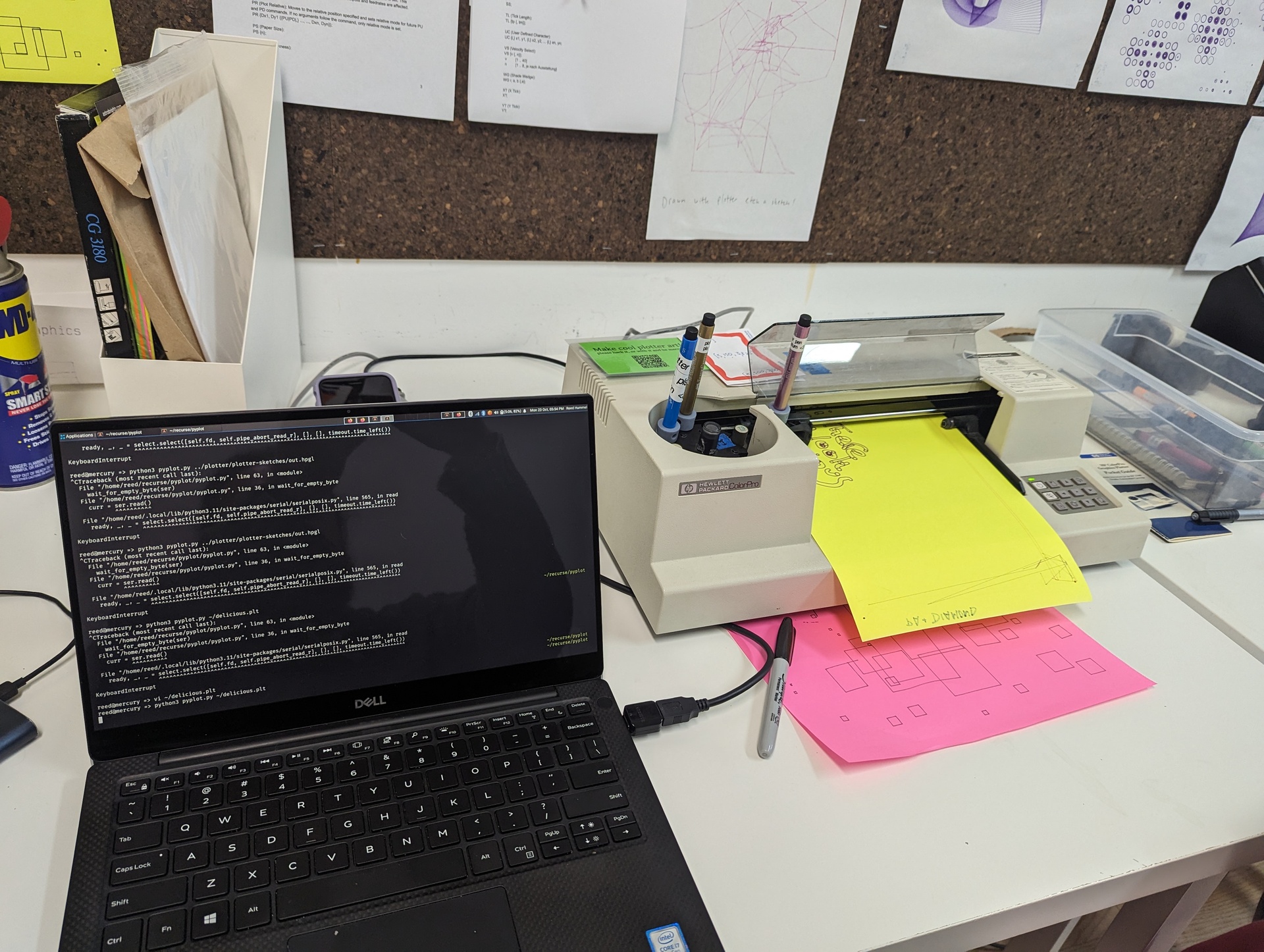

At the Recurse Center, I’ve been messing around with an old HP7440A pen plotter that’s kicking around the space (this seems to be a time-honored RC tradition from what I can tell.) It speaks HPGL, which is an old language specifically for plotters.

A peculiarity of the system is that it has a mere 60-byte buffer for all commands sent to it. Naturally, any modern computer will rapidly overflow it, and the resulting wacky movement of the plotter can wreck your drawing.

Today I was pairing with my friend at RC on getting the plotter to plot some HPGL that they converted from SVG. At first, we were just copying 60-byte sections from our file in, to verify that the file was at least valid HPGL. But we got tired of that pretty quick.

So… pyplot was born (inspired entirely by and partly based upon Wesley’s plotter-tools).

It’s around 80 lines of semi-original Python, built with the help of ChatGPT for the scaffolding.

This is a relatively straightforward script, with relatively little complex logic.

First, we need chunk(), which is what manipulates the

bare text of an HPGL or PLT file and produces an array of chunks that

can fit in the buffer. It’s just text and array mangling, with a little

additional complexity because we need to add an OA command

to know when the plotter has processed an entire chunk (OA

prompts the plotter to respond with the current pen position and status,

terminated by \r.)

After that, it’s as straightforward as iterating through our chunked commands and sending each one through the serial connection to the plotter.

I just hardcoded the plotter as /dev/ttyUSB0. Often, I

think for a small and straightforward interpreted script that’s geared

towards technical users, it’s reasonable to use in-code configuration.

So if you download this script and the plotter shows up as

/dev/whatevertheheck, feel empowered and change it :P

This question came up as we were pairing on this, and I think it is an interesting one, one that I don’t think I’ve ever fully considered?

So, to wikipedia! It strikes me as interesting that so many related communication standards are grouped under “serial.” I suppose it makes sense, as typically this type of communication is abstracted out to simply data-streams in most modern programming environments.

So really, in much the way everything works in *nix systems, it’s a file. With the caveat that unlike a file, data received or sent over a serial stream is ephemeral and doesn’t persist once it’s been read.

sidenote sidenote: I find it interesting that while serial behaves like a file, so too do files behave like serial, typically. They’re both examples of streams, that have limited-to-no notions of backtracking. The stream crops up everywhere, and I find it interesting that it’s one of the fundamental computing concepts that was glossed over in my university education, despite my uni having a very “learn the fundamentals, program in C, here’s how to write an OS scheduler” type of attitude. I think I remember one, maybe two lectures on streams.

Anyways, in this context serial is just the protocol that wraps the bytes we want to send to/receive from the plotter. The details of it don’t matter so much for us in this context (though they certainly can if you’re working more in the hardware domain), and can vary drastically between serial standards

Now, we just need to shove each chunk into the plotter, after which

we wait for the response from the OA command. The response

itself we don’t really need, we just need to know that the chunk of

commands that preceded that OA command have succeeded. Then

we are free to repeat the process, all until we run out of commands and

the program ends (actually on looking over the code again, it might just

hang indefinitely when the plotter finishes? I can’t remember and can’t

be bothered to go test it all out again.)

That’s what I made! Next I might take a closer look at vpype which has been recommended to me a number of times and looks quite exciting. When I return to Portland, I’ll need to find one of these plotters, or build my own. I’m particularly intrigued by what are termed winchbots or cablebots, detailed here in an excellent Hackaday roundup, which take up very little space and can draw on huge canvases (albeit slowly, at least at hobbyist grade.)